Tuesday, July 14, 2009

So.. what exactly is a slum anyway?

For the past 6 weeks i have been working with HMS, a UC Berkeley student run organization, that works on health and sanitation in the slum communities of Mumbai. While i have been in slums in other developing countries, I have never really known how to define a slum. A lot of my time here is spent reflecting on my surroundings and the realities of poverty, foreign aid, and everyday life in Mumbai "slums".

So, i will finally begin trying to relay my experience by trying to answer the question i am asked most often: "So what exactly is a slum anyway?"...

The United Nations agency, UN-Habitat, defines a "slum" as a run-down area of a city characterized by substandard housing and squalor and lacking in tenure security. In the past, the term "slum" has been used to refer to housing areas that were once respectable but have sinse deteriorated as their original dwellers move on to newer and better parts of the city. Today we use the term slum to also include informal settlements found in cities in the developing world.

According to the UN, one billion people worldwide live in slums and the number is expected to grow to 2 billion by 2030. The Indian government has announced that the number of people living in slums in India now exceeds the entire population of Britain!

As expected, people living in slum communities are generally very poor and often socially disadvantaged. Depending on the individual slum, the buildings vary from simple shacks/ shanties to permanent well-maintained structures. In densely populated areas like Mumbai, many slums growing vertically to include three or four story buildings, housing many families. Most slums lack clean water, electricity, sanitation and other basic services.

This summer, we have seen that slum politics are both intricate and complicated. Characterizing a housing areas as a "slum" often has harsh consequences for its inhabitants. Recently the UN-Habitat and the World Bank have been criticized for their 'Cities without Slums' campaign because it has led directly to a massive increase in forced evictions. In fact, many people have said that the recent fire in Behrampada, a slum that HMS has worked in since 2004, was started intentionally. one man i met from the British consulate told me "Well you know as well as i do that is valuable land". The deep, complex social structure of slums is also complicated and often difficult for outsiders to understand.

Currently, the education team is working mainly in the Dharavi slum, which is often cited as "the largest slum in Asia" with over 1 million residents. It has also become more well known because parts of Slumdog millionaire were filmed in Dharavi. Dharavi provides a cheap, but illegal, housing where rents in 2006, were as low as 4 US dollars per month. Until this trip i have not thought too much about slum economics, but i have learned that Dharavi exports a number of goods around the world.

The population of Dharavi is predominantly Muslim, including migrants from Gujarat who have established a potters' colony and tanners from Tamil Nadu who have set up a large leather tanning industry. Other artisans from Uttar Pradesh region (where i spent time last summer) started the ready-made garments trade. The total turnover is estimated to be between 500 million US dollars and over 650 million US dollars per year!!

This summer, we are piloting a handwashing education program in Dharavi schools which we hope will ultimately become self sustaining. I hope to write more about the program and my experiences soon. It's definitely been a roller coaster of a ride with high highs and low lows, but i am trying to appreciate every second of it. Thank you for your messages and emails - it is always great to hear from home.

BBC - Dhaaravi "Life in a Slum"

Love from India

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

Genocide. Have we learned?

I’m stuck in the UK... I left India for a couple of days to attend Oma’s funeral service in Amsterdam. On the return flight, weather, bad luck, and maybe a little bit of fate aligned to keep me in London for the night. So I’ve had a lot of time to catch up on thinking and reading.

In preparation fro visiting me in Cambodia, my mom is reading First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung. It is about her family’s experience during the time of the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian Genocide. The story is haunting. Almost overnight middle class families were forced to flee their homes and taken to the countryside. Universities, hospitals and banks were burned. Political and civil rights were abolished. Religion and music were banned. Even clocks and watches were destroyed. Any symbol of modernity, any un-communist aspect of traditional Cambodian society was to be eliminated. Teachers, doctors, lawyers, scientists, musicians, philosophers, and politicians were killed along with their extended families.

Minority groups, especially the ethnic Chinese were targeted. One Khmer slogan ran 'To spare you is no profit, to destroy you is no loss.' It’s hard to believe that this could happen in the matter of days, and even harder still to know that it happened only 35 years ago during the lifetime of my parents.

How did it happen? That part is possibly the most difficult to comprehend.

In 1962, Pol Pot, leader of the Cambodian Communist Party formed an armed resistance movement that became known as the Khmer Rouge and waged a guerrilla war against Prince Sihanouk’s government.

In 1970, Prince Sihanouk however, was ousted due to a US backed right wing military coup. Sihanouk retaliated by joining Pol Pot (his former enemy) in opposing the new military government. That same year, the US invaded Cambodia to expel the North Vietnamese from their border encampments, but ended up driving them deeper into Cambodia allowing them to ally themselves with the Khmer Rouge.

From 1969 until 1973, the U.S. intermittently bombed North Vietnamese sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia An estimated 150,000 Cambodian peasants were killed. As a result, peasants fled the countryside by the hundreds of thousands and settled in Cambodia's capital city, Phnom Penh. All of these events resulted in economic and military destabilization in Cambodia and a surge of popular support for Pol Pot.

By 1975, the U.S. had withdrawn its troops from Vietnam. Cambodia's government, plagued by corruption and incompetence, also lost its American military support. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge army, consisting of teenage peasant guerrillas, marched into Phnom Penh and on April 17 effectively seized control of Cambodia.

Leaders of the Khmer Rouge are only now facing trial.

I’d like to think we learn something from history. From the genocides that have taken place across the globe. From the lives of Jews, Tutsis, Muslims, and Hindus lost.

But killing continues and human rights violations are abundant.

I read about the protests in Iran and the UK and think maybe we have learned something. There are plenty of people fighting against violence, repression, hatred, and injustice...

Then again, I can't help but wonder, will it be enough?

Back in Bombay tomorrow. Project update soon. Love from London

Tuesday, June 9, 2009

Train tickets and Tumeric

I found Liza and Ana outside of the airport and we took a cab back to the apartment. It is in the Andheri district of Mumbai. It’s a really nice place – simple and clean. We have three bedrooms, three bathrooms, a living room, and a kitchen with a dining table. The landlord installed a water filter and a refrigerator earlier this week. There is even air conditioning and sporadic wireless internet in one of the bedrooms.

Yesterday morning Justin and I took the train to meet Sadaf (another HMS team member), in Mumbai Central. The line for train tickets was 2 hours long and we only had 20 minutes to get to Mumbai central if we were going to make it on time. We could either be late for our meeting or ride without a ticket and risk getting a 400rs fine (8 US$). A normal ride is about 5Rs. Justin already had a pass, so we decided that splitting the fine would be worth getting to Sadaf on time. My only request was that we ride together in first class so that if I got caught with a man yelling at me in Hindi for a train ticket, I wouldn’t be alone. Well, as soon as the train pulled into the station that plan flew out the window.

A stampede of men grabbed onto the already overcrowded first class car. Justin managed to get a hand inside the door and onto a pole to hang on to. There was no way I was going to try to squeeze myself into a car full of men. So at the last second I ditched justin and ran to the women’s car (always directly behind the first class car). It too was completely packed, but I was able to get one foot on board as the train pulled away from the station. Some of the other women pulled me all the way inside the car. I managed to get off on the correct stop and found Justin on the platform. I smiled “I didn’t get ticketed”. Just as I spoke a man in a white collared uniform shirt tapped Justin on the arm. Instinct told me to keep walking. I didn’t look back until I was a good fifty feet away. Justin had pulled out his pass and was showing it to the official. When he finally caught up with me we gave one another a look of relief and laughed all the way out of the station.

After meeting with one of Bombay’s Municipal schools for our project, Justin and Sadaf told me that they had found a woman close to where we live in Andheri that had agreed to give us cooking lessons. So from 3 to 6pm I was in a stranger’s kitchen learning to make things like Aloo Palak, Jeera rice, and three different kinds of Daal. It was so much fun. We ended up making a total of 8 different dishes. Watching Nalini cook was like watching a magician. She would throw ingredients into a pan – cumin seeds, red chili powder, onions, tomatoes, a hint of cinnamon and before we could say Tumeric (which seems to be in everything) she was handing us a spoon to taste her creation. Everything was phenomenal! We have our second class later this week.

Today we have a meeting with PSI (Population Services International) and will be running some errands around the city.

Love from Mumbai.

Friday, May 29, 2009

E waste. aka Agbogbloshie. aka "wo ho ye fe paa"

Sunday, December 14, 2009

It was the day before our flight back to the US and Miriam and I had one last adventure ahead of us. She had read about an E-waste scrap yard, aka dumpsite, in Accra and wanted to see if we could find it. We once again jumped in the back of a trotro, not really having any idea where we were headed, but as usual people we met on the way pointed us in the right direction. We went from one trotro station to the next, finally figuring out which one had cars that would drop us off near the waste site. We told people we were trying to get to Agbogbloshie – the name of the scrap yard (yeah, try saying that three times fast!). We were directed to a trotro in the far corner of the station. It was a trotro unlike any other I had ever been inside. The doors opened in the back of the van and there were no windows and no way to communicate with the driver. There were benches rigged to both sides of what felt like the back of a cargo container. The van was full except for one seat. We had no idea when the next car would come so we told the mate that we could make it work. He seemed slightly amused as he watched Miriam and I climb over the other passengers and squeeze ourselves into the tiny space left in the middle. Their faces changed from confusion to surprised approval as I sat down and motioned for Miriam to sit on my lap.

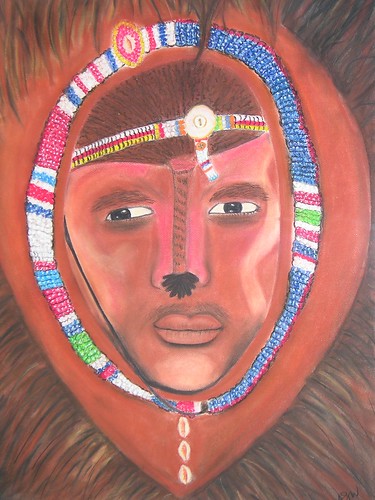

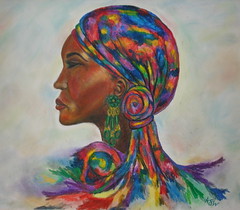

Once we were on the road, I finally had a chance to survey the other people in the car. There was a man in long pants and a tattered dress shirt, an older women with crocked teeth smiling at us, a baby strapped to the back of its mother – head bobbing up and down with the movement of the car and of course a number of beautiful women. There was one woman in particular that I literally couldn’t take my eyes from. She was breathtakingly beautiful. She wore a typical full length Ghanaian dress, tight around her hips and flared at the ankles. Her head was covered with a piece of matching cloth tied up and knotted around her hair. I remember thinking that she looked so calm and glamorous sitting in the back of that car. I imagined where she was going – it wasn’t Sunday so it couldn’t have been church. A party? Maybe a wedding. Ya, that’s it, a wedding. The trotro came to a stop and brought my daydreaming to a halt. One by one we filed out of the van, thankful for the fresh air. Now what? We had no idea where we were going and we weren’t exactly sure how to tell people we were looking for a waste site. We decided to wander. We walked only for a couple of seconds before we noticed trash piled alongside the road. I glanced across the street at what looked like a river of sewage lined with trash and metal parts. We had found it.

We walked into the scrap yard – a mixture of dirt and broken computer parts under our feet. The smell of burning trash and plastic welcomed us. We were both in sandals. Maybe I should have worn shoes? A little boy running around with bare feet interrupted this thought. There were broken motherboards and CDs, discarded bicycle frames, refrigerators, broken cars, rusting piles of metal, and rejected ovens and computers. We walked past a group of young men behind a gated off section of the yard. The sound of hammering and work stopped as they saw us approach. A couple of the braver ones came running out to greet us. I wasn’t sure how we were going to be received – as foreigners? intruders? I should have known we would be treated like friends. We couldn’t communicate with words and as we held out our hands to greet the young men, they hesitated. One of the men showed us his palms – they were covered in filth from working with the scrapes and wires. My heart sank a little as I glanced at my own perfectly Purell-ed hands. He didn’t want to get them dirty with his own. Instead they smiled and waved as we continued further into the yard.

We walked into the scrap yard – a mixture of dirt and broken computer parts under our feet. The smell of burning trash and plastic welcomed us. We were both in sandals. Maybe I should have worn shoes? A little boy running around with bare feet interrupted this thought. There were broken motherboards and CDs, discarded bicycle frames, refrigerators, broken cars, rusting piles of metal, and rejected ovens and computers. We walked past a group of young men behind a gated off section of the yard. The sound of hammering and work stopped as they saw us approach. A couple of the braver ones came running out to greet us. I wasn’t sure how we were going to be received – as foreigners? intruders? I should have known we would be treated like friends. We couldn’t communicate with words and as we held out our hands to greet the young men, they hesitated. One of the men showed us his palms – they were covered in filth from working with the scrapes and wires. My heart sank a little as I glanced at my own perfectly Purell-ed hands. He didn’t want to get them dirty with his own. Instead they smiled and waved as we continued further into the yard. The river of sewage seemed to separate the site into two parts: the side on which the e-waste was dumped and kept, and the side on which the people live. On the side opposite of where we stood, shanties lined the ‘river’. People actually live here. Raised their families here. This was their backyard. We noticed a small makeshift ‘bridge’ (slats of wood) connecting one side to the other. As we got closer, another group of young boys motioned for us to follow them across. Needless to say we both hesitated, imagining ourselves falling in the smelly river of human and manmade waste. We carefully balanced on the first board. One of the boys looked back and said encouragingly “It’s okay. Go small small” translating into take it slow, one step at a time. We made it across the bridge and climbed up the edge of the embankment. We walked along the front of the shanties. Some images that stuck with me: a small boy defecating on a pile of burned trash, a group of women sitting around a table playing a board game, a little girl rummaging through a mound of waste – a red streamer around her neck.

The river of sewage seemed to separate the site into two parts: the side on which the e-waste was dumped and kept, and the side on which the people live. On the side opposite of where we stood, shanties lined the ‘river’. People actually live here. Raised their families here. This was their backyard. We noticed a small makeshift ‘bridge’ (slats of wood) connecting one side to the other. As we got closer, another group of young boys motioned for us to follow them across. Needless to say we both hesitated, imagining ourselves falling in the smelly river of human and manmade waste. We carefully balanced on the first board. One of the boys looked back and said encouragingly “It’s okay. Go small small” translating into take it slow, one step at a time. We made it across the bridge and climbed up the edge of the embankment. We walked along the front of the shanties. Some images that stuck with me: a small boy defecating on a pile of burned trash, a group of women sitting around a table playing a board game, a little girl rummaging through a mound of waste – a red streamer around her neck.We walked past a group of men and women sitting on a bench. To my amazement one of them was the beautiful woman from the trotro. I was shocked to see her in her stunning dress and jewelry sitting in the middle of the scrap yard. She motioned for us to come and join them. We sat down on the bench and spent the next couple of minutes trying to remember as much Twi as we possibly could. After we ran out of greetings I clumsily blurted out “Wo ho ye fe paa” – you are very beautiful. The women smiled and blushed. Her friends laughed but agreed. We waved goodbye and continued on. There was a large truck overflowing with men and flags – red, white, back, and green. The sound of a bullhorn told us it was part of an NDC rally (the presidential election was still going on at this time).

I’m not sure what I had expected, but as we walked through this waste town I felt more and more confused. I couldn’t see the toxic chemicals, the chlorinated dioxins, or the phthalates that were slowly poisoning these people. All I could see was life. People doing the best they can with what they have. People welcoming strangers into their home. I don’t know when in my mind these people whom I had heard about, burning electronic cables, started being casualties instead of people. While Miriam and I walked out of the scrap yard I made a promise to myself: No matter how awful or unfair someone’s situation, no matter how hard people fight and fail to change it, never again will I assume that a person is a casualty, a victim, or a martyr. Never again will I assume that a person is anything less or different than a human being living his life the best way he knows how.

I am reminded of my Cameroonian friends Flynn and Brian and how they didn’t know me, but they took care of me. “You are my sister and I am your brother” was the only possible explanation I received or needed. Reflecting on this almost two years ago, I wrote, “We are family because we are human beings - we share a world, a history, and a vision.” Today I am a little more pragmatic and maybe a little less naïve. I have such mixed feelings on what actions foreigners, especially westerners, should take in order to “Save Africa” (See previous post). However, I do hope that someday we can stand up to the electronic companies in developed countries that are poisoning Ghanaians in Agbogbloshie, not because they are helpless victims, but because they are people, which make them family.

For more information:

Download full Greenpeace document here

Ghana's growing e-waste trade, BBC

UK's e-waste continues to be dumped in Ghana, Nigeria despite public outcry, Ghana Business news

More videos

Do you do voodoo?

Miriam and I had heard that there was a Voodoo market in Accra. Some of our friends had even tried to find it a couple of time. There was apparently a voodoo section at the “Timba market” in Jamestown. Without thinking too much about it, we decided to ask around and see what we could find. The man who led us to the top of the lighthouse pointed down the main road leading through Jamestown. We asked if we could walk but he told us the market was too far – we needed to take a cab. But we felt empowered after visiting the slum fishing village and decided to at least walk as far as we could. We strolled down the road getting lost in deep conversation (a definite theme when we are together). We asked a couple of friendly faces if we were headed in the right direction. Before we knew it a women had offered (through a third party since she didn't speak English) to take us there.

She walked quickly. Miriam and I must have looked like two straggling ducks trying to keep up with their mother. The women looked back at us every so often to make sure we were still behind her. She stopped in front of a dirt area connecting two larger buildings that faced the main road. There was a tall wooden fence between the buildings and a couple of cars parked in front. She motioned with her hand that we should follow her. I looked at Miriam confused and uncertain. She motioned again and disappeared through a small cutout in the wooden fence. As we got closer we could see the sign hanging above the cutout doorway. “No trespassing. Violators will be prosecuted.” Miriam and I shared another quick glance and a mischievous smile. One after the other we ducked through the doorway and hurried to catch up with the woman who was quickly gliding through the small passageways.

It was the most astonishing thing – there was a whole market community behind that fence. We walked through the narrow dirt paths that were lined by wooden stands. People were selling everything a person could possibly need. Our curiosity couldn’t keep up with our legs. We thanked the women for her help and said goodbye. We were on our own, completely lost in the middle of the market. We figured we would start asking around about the supposed voodoo section. We weren’t quite sure how to ask someone if they knew where we could find gigi charms? Did they even call it voodoo? Would that be offensive? We were surrounded by bags of nuts and bolts - the home depot of Accra. The men were eager to help us find whatever we were looking for. I got the feeling it wasn’t every day that two oburoni women came to visit. After the appropriate greetings and a little bit of flirting, we tested the water – “do you know where we can find voodoo?” The men looked at each other, thought for a moment… “Medicine. You are looking for medicine. Follow me” Before we knew it we were off and clumsily chasing another graceful Ghanaian who had probably grown up weaving in and out of market passageways (I almost got knocked out multiple times by men carrying wood on their heads). As we moved through the market there was a buzzing sound that kept getting louder and louder - the sound of electric saws cutting wood. There was sawdust everywhere, the cutting of Timber. All of a sudden it made sense… “Timba Market” = Timber Market.

We finally reached the section of the market we had been looking for. Skins, bones, hair, bark, shells, coins, and wooden dolls were hung and stacked high inside the stalls. We couldn’t believe that we had actually found it. We walked around and stopped at a stall owned by a woman named Mercy. She explained what everything was used for. She explained how to use coins and red string to make wishes, which dolls were used for fertility, and how to get rid of illnesses. By asking questions, we learned that generally speaking, everything could be used for anything. I asked Mercy what was used for love. I bought some dried up seedpods that are supposed to be brewed into tea and given to a lover - the perfect wedding gift for my sister. We had such a fun time looking around and talking to the vendors. We found our way out of the market. Sitting in the back of a cab as it drove away, we knew we would never be able to explain where the market was located. We probably couldn’t even find it again ourselves. As we recapped the events of the day, I realized once again that it was not just the destination that was inspiring; it was the entire journey.

love from Tustin.

Monday, May 4, 2009

A day to last a lifetime in the Jamestown slum

The last time we were in Jamestown was during the first week of orientation. We toured Accra in an air-conditioned charter bus – it could barely fit through the streets on the outskirts of Accra’s largest slum town. I remember sitting with the side of my face pressed up against the window watching life go by. Women hanging laundry – torn and tattered yards of fabric to dry. People cooking over open fires – black smoke dancing with the trash and dirt picked up by the breeze. I remember seeing a small schoolgirl in a blue and yellow uniform trip and fall – scattering her books in the street. I was an observer that day – removed from the emotions, passions, and monotony of every day life in the Jamestown slum. We weren’t allowed to get out of the bus and even if we had been I’m not sure if I would have been able to shed my bystander skin. After spending almost 5 months in Ghana, I had learned there was a significant emotional difference between observing and engaging.

Miriam and I decided that with only a couple days left in Ghana it was time for us to go back to Jamestown and explore a part of Accra we had not yet seen. We took a tro tro to Jamestown and wandered around until we found the Jamestown lighthouse (one of the landmarks mentioned in the tour guide). We ran into a man that said he had keys to go to the top. It looked closed, deserted even – except for a group of small kids playing a game of foosball right in front. But we followed him anyway. Sure enough our new friend found the woman in charge. After collecting her fee, she let the man lead us to the top of the lighthouse. What a view.

We could see all the way down the main road and the shanties by the water. A strange juxtaposition – the small confined spaces enclosed with scrap wood and metal. The infinity of the ocean. After observing from the sky, we agreed it was time to engage on the ground. We decided to walk around the slum fishing village right on the water. Everyone stared as we stepped over fishing nets and under hanging sails and tarps, moving further into the heart of the small fishing community. It was uncomfortable and not all of the stares were friendly. I felt out of place and a bit nervous. I couldn’t tell if it was because of my prejudices or theirs. Probably both. I was entering a world i will never completely understand with a life and a background they too do not know. I tried to escape my prejudices and my differences. I smiled at the men repairing the nets and made small talk with the women we passed. Wo ho te sen? Ye fre me Abeena. Once again our limited amount of Twi served us well. I began to feel the tension between my shoulders slowly disappear.

We could see all the way down the main road and the shanties by the water. A strange juxtaposition – the small confined spaces enclosed with scrap wood and metal. The infinity of the ocean. After observing from the sky, we agreed it was time to engage on the ground. We decided to walk around the slum fishing village right on the water. Everyone stared as we stepped over fishing nets and under hanging sails and tarps, moving further into the heart of the small fishing community. It was uncomfortable and not all of the stares were friendly. I felt out of place and a bit nervous. I couldn’t tell if it was because of my prejudices or theirs. Probably both. I was entering a world i will never completely understand with a life and a background they too do not know. I tried to escape my prejudices and my differences. I smiled at the men repairing the nets and made small talk with the women we passed. Wo ho te sen? Ye fre me Abeena. Once again our limited amount of Twi served us well. I began to feel the tension between my shoulders slowly disappear.

It was as if the more relaxed I became, the friendlier the people treated me. Word spread that there were Obrunis in the village speaking Twi. Before we knew it we were in the middle of the small slum village and approaching the peer. We asked the group of men sitting near by if we could walk on it and “come right back”. They laughed and smiled. Permission granted. Once again we dodged piles of nets, distracted by the young men running and jumping off the small wooden peer. They did flips and tricks, each one flashing a smile before catapulting their naked bodies into the air. We sat on the edge with our feet dangling over the water. Some boys our age came to chat with us. I was no longer uncomfortable or nervous. It constantly amazes me what a smile and an open heart can do.

After about 15 or 20 minutes an older man came over and explained that women were not allowed on the peer. Miriam and I looked around and then at one another. There wasn’t another female in sight. Oops. There are two important things that are relatively easy to forget but that we will never be able to escape: We are white and we are women. We apologized, said goodbye to the boys and left. As we walked out of the slum people smiled and waved. Yebeshia Bio - We will meet again soon. Despite the unlikelihood that their greeting would hold truth, there was warmth in their smiles and sincerity in their eyes.

After about 15 or 20 minutes an older man came over and explained that women were not allowed on the peer. Miriam and I looked around and then at one another. There wasn’t another female in sight. Oops. There are two important things that are relatively easy to forget but that we will never be able to escape: We are white and we are women. We apologized, said goodbye to the boys and left. As we walked out of the slum people smiled and waved. Yebeshia Bio - We will meet again soon. Despite the unlikelihood that their greeting would hold truth, there was warmth in their smiles and sincerity in their eyes.love from Berkeley.

Sunday, February 22, 2009

It's a small world after all.

He was short with dark dreaded hair to his chin. A metal marijuana leaf hung around his neck on a beaded chain - red, yellow, and green – the colors of Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast (red to remember the blood that was shed, yellow for gold, and green for the natural resources and land). It wasn’t so much the “rasta” look that gave him away or even the dimples that complemented his wide smile. It was more of an attitude. An aura. He seemed comfortable, at ease, almost like he owned the place. He introduced himself. “Ye fre me Ablo” (They call me Ablo). “It's nice to meet you Ablo. By any chance to do you know Aruna?”

Aruna was our Kora teacher. He came to Legon on Sundays and sometimes we would go to Kokrobite, where he lived, to see him perform. Turns out Ablo is who Aruna has been talking about for the past two months. Ablo lets Aruna stay with him in Accra after he finishes with his lessons in Legon. “Aruna is my brother.”

Ablo insisted on showing us around. We followed him through the village and the adjacent dumpsite – hiking over mounds of dirt and trash. He lived just on the other side of the lot. We approached a small one-bedroom hut – no furniture, only a floor to sleep on and a stereo for listening to music. A section of the wall was lined with glossy photos of musicians, handmade Koras, foreign students, and friends. A tall man sat on a bench outside the hut. Wooden slats and small gourds surrounded him while he diligently worked on a xylophone. Building it from scratch.

Love from Berkeley.

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Accra Adventues

This is what the trotro mate, (the driver’s wingman – so to speak) while hanging out the side of the van, yells when passing by a station so that people know he is going to Accra.

We only had a couple days left in Ghana and for the past week we had all been trying to figure out how best to use them… Can we get all the way up to Burkina Faso? Can we make it to mole national park in the north? How crazy would we be to go to Cote d'Ivoire? We finally decided that to go anywhere far away would just be too much. Besides, we had lived in Accra for four and a half months and we had still so much of the city to see. So Miriam and I set off to the center of the city – not having a plan and barely a destination. But the places we went, the people we met, and the things we saw… well, I wouldn’t trade them for anything. And so, here they are, my last days in Accra, the Accra adventures – the lasting impressions…

Thursday, Dec. 11, 2008

Miriam and I had both been to the art market near Tema station before. It’s a tourist trap. A place where you can buy Kente cloth without ever visiting Kumasi, overpriced drums and figurines, masks that have never been worn, and swords of all kinds. As soon as you step into the dirt parking lot you are bombarded with offers. People from all directions swarm to you with their beaded jewelry and instruments. Although the market is well done - each vendor has their own stall under a high, wooden roof – it is still intimidating.

We got off at the Tema Trotro station and started walking. We couldn’t remember exactly where the center was, but we decided to follow our noses until things began looking very unfamiliar. We stopped to ask for directions from an older man who spoke very little English. He understood “art center” and our hand gestures of drums and paintings. He spoke quickly and pointed with both hands. Left then right? Right then left? Follow which road? He could see the confused expressions on our faces. We started to laugh and he motioned for us to follow him. In typical Ghanaian fashion, he walked with us until he could point us in exactly the right direction and then turned back and continued along his own path.

We made it to the market unscathed and began our search for small brass weights. We had bought a children's book that explained how and why these small figurines were made and wanted to find some of the small weights to go with the book. We worked our way to the back of the market and settled on a small stall where we could practice our Twi negotiating skills.

“Me pe baako” – I want only one. “Oh me adamfo. Te so” – Oh My friend. Reduce the price. The awura (seller) laughed at our broken use of his language, impressed at our knowledge. And so the bargaining began. He gave us a price. “Ahh (it’s important to pretend to sound shocked) Dabbi Dabbi Dabbi” – It’s too much. Too expensive. We gave him a counter offer. “Oh my sister’s 5 cedi? It’s no good. No good. 10 cedi is good. 5 cedi is no good.” We finally settled on a price for our small figurines, laughing and joking the whole time.

“What about some ‘giggy giggy’?” He pointed to the small statues of men and women in compromising sex positions. Miriam and I looked at one another and started to laugh. “what? You no want giggy giggy? I give you good price”. “My brother” I replied, “giggy giggy to so” - ‘to so’ is one of the most important expressions. It literally translates into ‘add a dash’. For example if you are buying 10 tomatoes and say ‘to so’, the seller will usually add a couple extra free of charge. He started laughing and couldn’t stop. I don’t think anyone has ever asked him to add a dash of ‘giggy giggy’. We waved goodbye and kept working our way to the back of the market.

The farther back we went, the more friendly and easy going the people seemed. There was less pressure to buy things and we weren’t noticed quite as much. People were busy chatting and working away. We made it to the last stall in the back. It lined a dirt trail that continued behind the market area. We kept walking. Before we knew it, we had entered a small village-like community. Who knew there were people living behind this popular tourist destination we had been so many times before? There were small doorless shacks with people building drums, a tiny bar where a group of men where having drinks on plastic chairs. There was even a soccer game going on right on the edge of the bluff with a beautiful view of the ocean. This next to a huge trash dumping ground to our left and a couple of chickens and goats running around. We just stood there for a minute in awe of our surroundings.

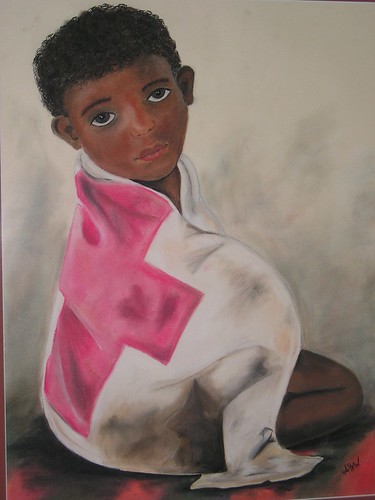

Right in front of us there was a group of about 5 children between the ages of 3 and 7. They were forming a line for something. Then, in an instant, one of the older children raced buy us, pulling an old beaten up suitcase behind him. The top flap had been torn off so that it was no longer a suitcase but a wagon. Sitting inside the wagon/suitcase was a small child no older the four. Sitting on her knees and holding on to the sides of the suitcase - hanging on for dear life. Smiling from ear to ear. The other children were lining up to be pulled in the suitcase. They whizzed back and forth in front of us, taking turns pulling and being pulled - Laughing all the while. It’s one of those images that will be forever burned in my memory. Wherever you go, kids will always be kids.

After walking around a little more, saying hello to all of the people, showing off our Twi, we began to head back to the art market. We walked by a young man who looked uncannily familiar. “Doesn’t he kind of look like Aruna?” Miriam asked. “That’s funny. I was just thinking the same thing.” It wasn’t Aruna. But it was his best friend. Someone we had heard much about, but never met.

To be continued…